The USDA has forecast an 8.77% decline in winter wheat acres for the 2024/2025 marketing year and a 6.67% decline in total wheat acres. The decline in planted acres for both winter wheat and all wheat would be the seventh-most drastic in the last 40 years. However, as I travel through wheat country, I explain to farmers why a smaller pullback in wheat acres is more likely.

Winter wheat acres increased by about 3.42 million acres, or 10.27%, in the 2023/2024 marketing year, the most acres since 2015/2016. The almost 9% decline in expected 2024/2025 winter wheat acres is partly backed by rising U.S. ending stocks of hard red winter (HRW) wheat (the predominant winter wheat class). For example, HRW ending stock estimates for the 2023/2024 crop have grown about 24% over the last 14 months and are expected to increase an additional 33% for the 2024/2025 crop.

The steady increase in ending stocks has correlated with a steady decline in wheat prices of all classes, which is why the market consensus is for acreage to decline sharply. However, these estimates somewhat overstate the decline in acres, and I expect wheat acres to decline only slightly for several reasons.

The tighter ending stocks for wheat give some indication that a supply hiccup or demand boost could quickly improve the price outlook for wheat.

Wheat Stocks Argue for Only a Slight Decline

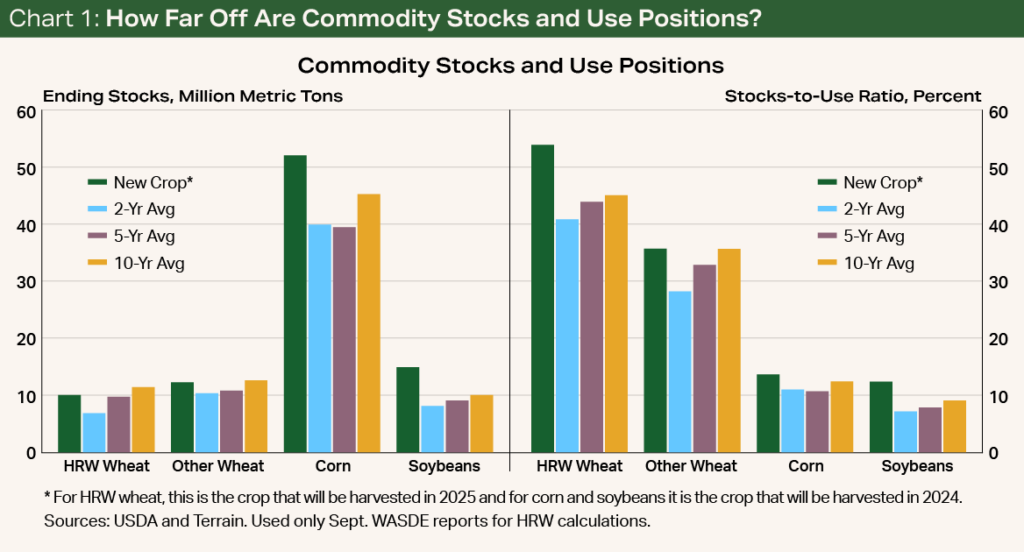

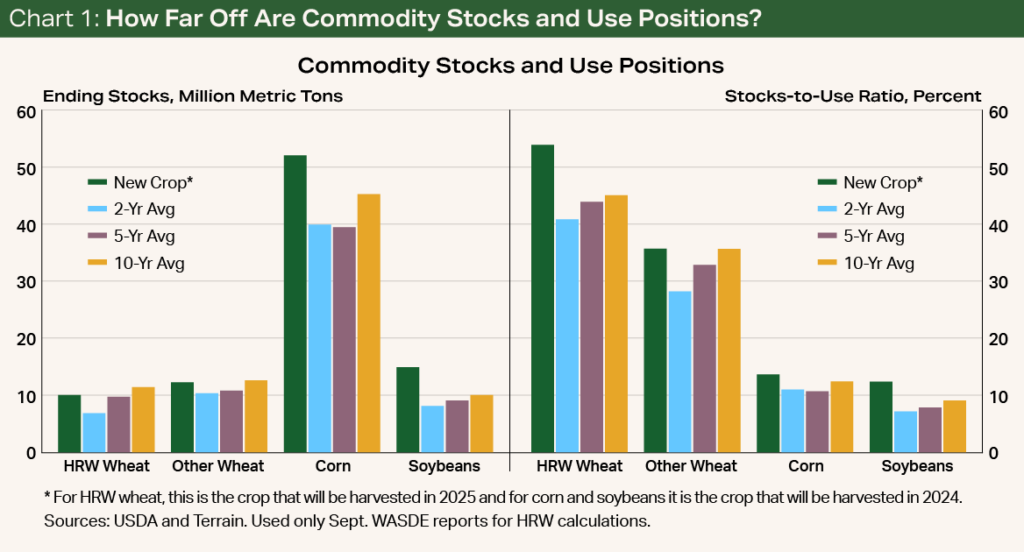

First, the estimated 2024/2025 ending stocks for HRW wheat are only 2.6% above the five-year average and 12% below the 10-year average. Additionally, ending stocks for all other wheat classes are only 13.5% above the five-year average and 2.3% below the 10-year average. Comparatively, ending stocks for the incoming corn and soybean crops tower over the five- and 10-year averages (see Chart 1). The tighter ending stocks for wheat give some indication that a supply hiccup or demand boost could quickly improve the price outlook for wheat.

Stocks-to-use ratios are closer among the crops:

- The 2024/2025 HRW stocks-to-use ratio is 22% higher than the five-year average and 19.5% above the 10-year average.

- The ratio for all other wheat classes is 8.5% above the five-year average and 0.2% above the 10-year average.

- The current-crop corn stocks-to-use ratio is 27% above the five-year average and 9.8% above the 10-year average.

- For soybeans, the ratio is 57% above the five-year average and 38.3% above the 10-year average.

The stocks-to-use ratio is helpful for understanding both supply and demand. In the case of wheat, the HRW stocks-to-use ratio is similar to corn and soybeans, but all other wheat stocks-to-use ratios are more favorable.

Wheat ending stocks for global competitors and top importers are also favorable for supporting U.S. wheat prices.

Put differently, farmers in winter wheat-growing areas will likely feel as confident about the upside potential of wheat as they will about the next (2025/2026) corn and soybean crops. In certain areas, some farmers may be tempted to plant additional spring wheat acres in 2025 if corn and soybean stocks remain onerous. Therefore, while wheat acres may decline, it is unlikely that they will decline as much as the USDA estimate.

Tight Global Supplies and a Key Cost Advantage

Second, wheat ending stocks for global competitors and top importers are also favorable for supporting U.S. wheat prices.

USDA projections for wheat ending stocks for Russia are at a multiyear low, and ending stocks for other top global exporters are below recent averages. Additionally, ending stock levels for the top 10 U.S. wheat importers are in line with recent averages. The tighter global supplies could provide some price upside, particularly if the U.S. dollar can weaken from its strong levels and improve the export outlook.

The USDA estimates that the operational costs for wheat in 2025 will be $274 per acre less than corn and $66 per acre less than soybeans.

Inflation-adjusted net cash farm income for wheat, corn and soybeans is projected to fall sharply in 2024, with many experiencing the lowest income levels in more than a decade (“First Look: 2023 Farm Profitability by State”). However, given that wheat simply costs less to produce, the crop may find unexpected favor in an environment of constrained liquidity, tight margins and somewhat elevated interest rates.

The USDA estimates that the operational costs for wheat in 2025 will be $274 per acre less than corn and $66 per acre less than soybeans (see Chart 2). Following a crop year of very thin or negative profit margins and potentially constrained lines of credit, wheat farmers are less likely to rotate out of wheat and into more expensive crops.

The one caveat is that 50% of traditional winter wheat acres were in drought as of September 24, compared with 47% last year, according to the USDA. If the drought over winter wheat country worsens, some farmers may forgo winter wheat planting and rotate instead into sorghum, corn, soybeans or possibly cotton in the spring. In certain areas, durum and spring wheat may also be a viable option.

Although the USDA expects a sharp decline in wheat acres, there is good reason to believe that the decline will be less pronounced. Farmers choosing to keep a higher share of wheat in their rotation need to keep an active eye on prices and look for times when they can lock in profits, especially if acres come in higher and pressure already subdued wheat prices. Some general farm stress could be greatly alleviated if the wheat portion of a farmer’s rotation can be price-protected going into the 2025/2026 corn, sorghum, soybean and cotton planting season.

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of AgCountry Farm Credit Services,

American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.