As I have traveled the dirt roads of rural America, farmers have increasingly asked about the economic alliance known as BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and new entrants). Most of the questions have centered on the scale and scope of BRICS, whether BRICS can dethrone the U.S. dollar, and whether U.S. farmers can expect an impact to agricultural exports.

A Brief BRICS History

In 2001, a Goldman Sachs economist (Jim O’Neill) wrote a white paper that focused on the emergence of Brazil, Russia, India and China as the next world superpowers.1 Russia eventually convened the group of nations, and thereafter South Africa was added to the mix to form BRICS. In 2024, the group officially expanded to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Indonesia has also reportedly been upgraded to full membership status.2

So far, the group has met annually since 2009 to align on economic policy, financial policy and, it is assumed, policy for key international groups (like the United Nations). Recently, the group has been outspoken about creating its own financial system and breaking further from Western economies.

These Aren’t Economic Lightweights; Take Them Seriously

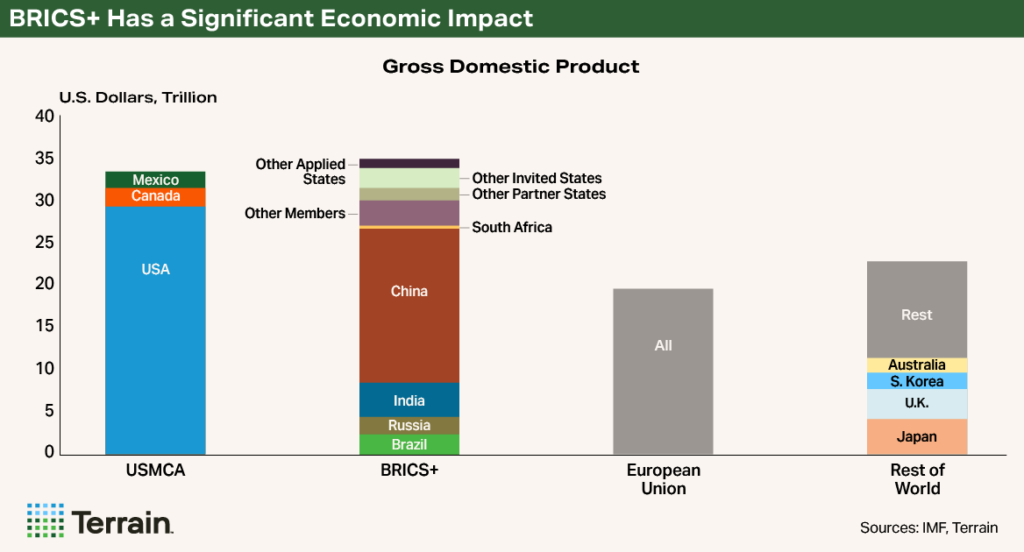

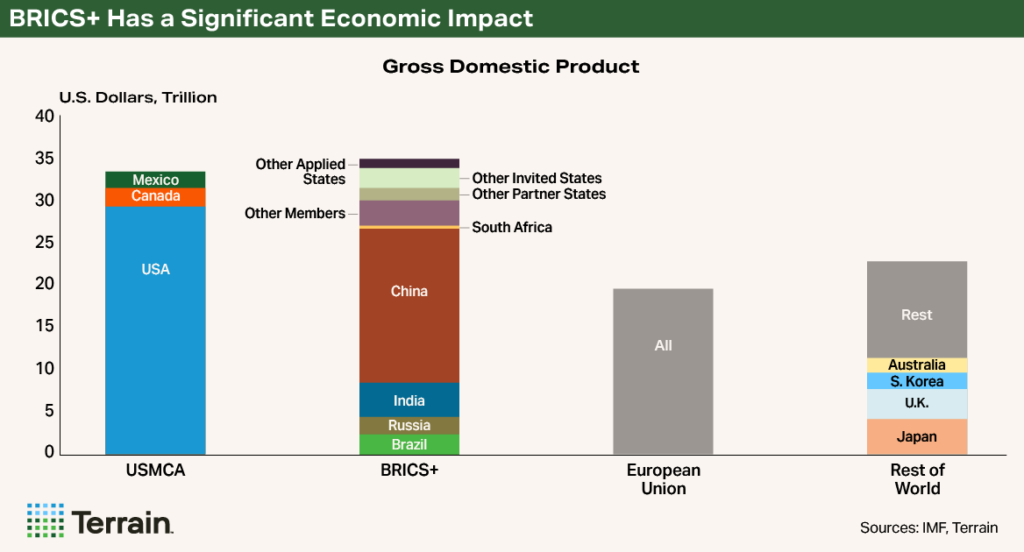

BRICS+ (the full group of members, partners, observers and applicants) is collectively large. For example, the combined nations in BRICS+ have a total GDP slightly above that of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). (Because BRICS+ is an alliance, the USMCA is used for comparison purposes versus its individual country names.) Specifically, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that the total GDP of BRICS+ was about 5% larger than that of the USMCA in 2024 and forms over 30% of global GDP.3

The IMF also projects BRICS+ to see faster growth in GDP than the USMCA. For example, the IMF estimates that by 2029, the BRICS+ total GDP will be 16% larger than the USMCA’s; however, much of that growth is dependent on China and India.3

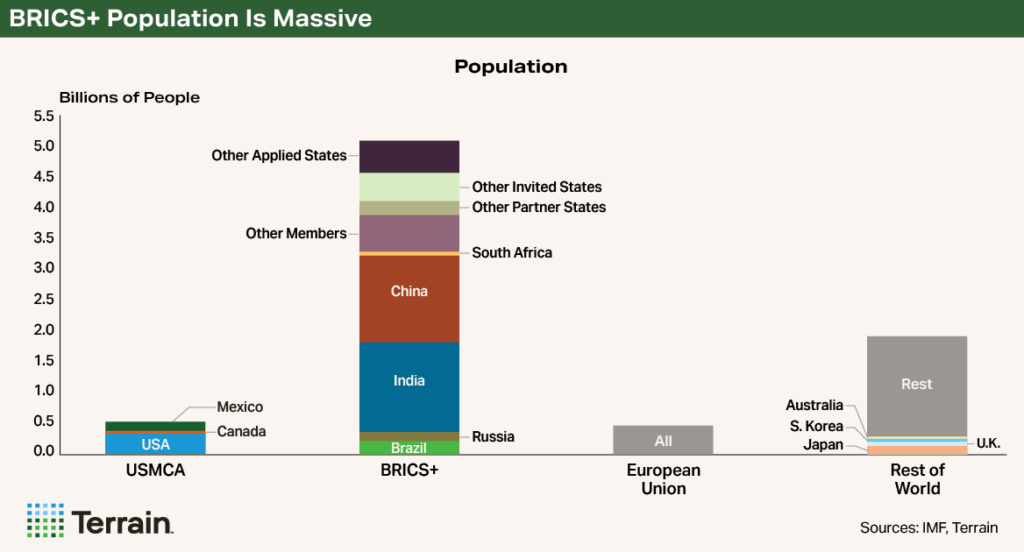

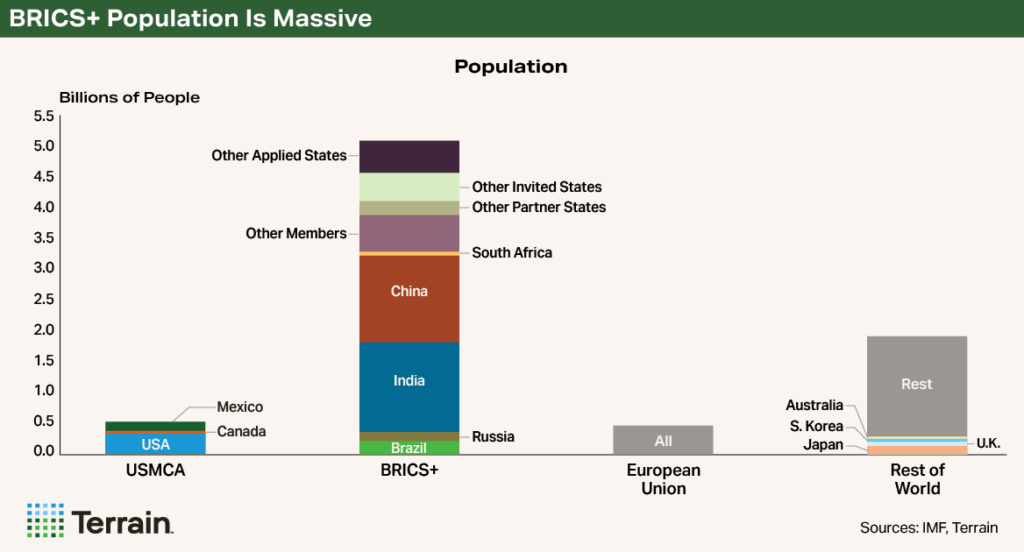

BRICS+ nations also make up the majority of the global population. China and India alone make up about 36% of the global population; adding the rest of BRICS+ brings the calculation to nearly 64%.3 The IMF also expects the BRICS+ population to grow in the coming years, even though some countries such as China and Russia have already experienced peak population.3

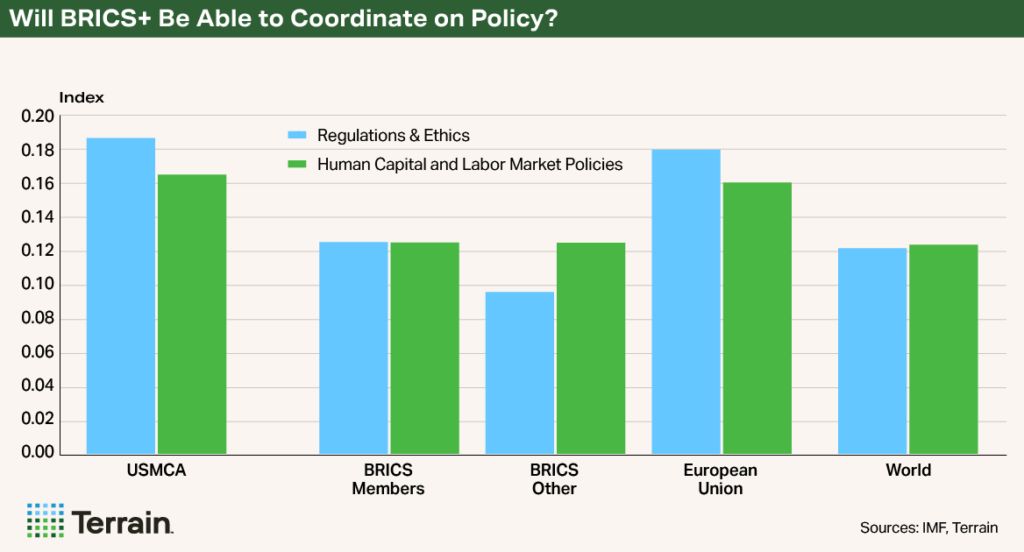

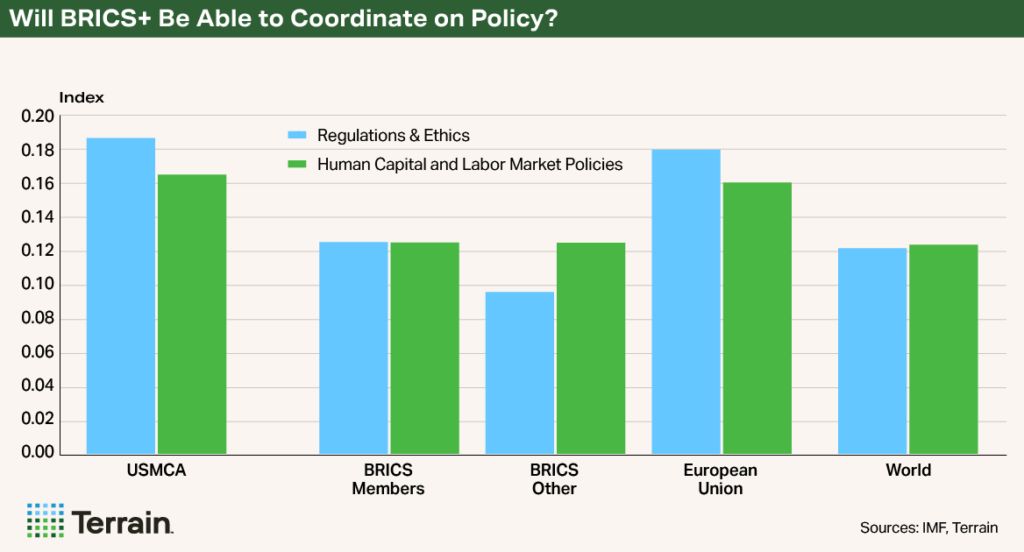

The challenge for BRICS+ will be to get more than 30 nations to agree on policy and coordinate in a frictionless manner. The difficulty of coordination is enhanced by the fact that the countries in BRICS+ are historically less “economically open.” For example, the BRICS+ nations have some of the lowest scores for economic regulations and ethics and human capital/labor market policies.3 However, given the economic punch that the combined power of BRICS+ can deliver, the group should be taken seriously.

Implications for the Farm Economy: Q&A

The BRICS+ alliance has many geopolitical and economic tentacles, but in many senses the group itself is quite young. Consider that the five core members have been together since 2010, significantly less time than NAFTA (the U.S., Canada, Mexico) (1994), the European Union (1993), and Mercosur (South American trade bloc) (1991). Therefore, policies, procedures and economic ties are still being developed, and the full weight of these policies will likely be felt further down the road.

However, when I talk to farmers, they have three common questions that reflect near-term concerns:

Question: “Can BRICS+ dethrone the U.S. dollar as the chief global currency?”

Answer: At various points, BRICS+ has tried to create its own currency, but those plans appear to be tabled.4 China will likely continue to trade more in Chinese renminbi to avoid using the U.S. dollar, and some of the other BRICS+ countries may follow. However, the saturation of the U.S. dollar will be difficult to break. For example, the Federal Reserve estimates that from 1999 to 2019, the U.S. dollar accounted for 96% of trade in the Americas, 74% of trade in Asia-Pacific, and 79% of trade in the rest of the world.5

Other sources indicate that the U.S. dollar was on at least one side of the trade in more than 90% of global transactions, including BRICS+ countries.6 As a result, the IMF estimates that the U.S. dollar claims nearly 60% of the composition of global foreign exchange reserves, down from previous years but still dominant.7 Therefore, while BRICS+ may try to trade less in the U.S. dollar, the group is unlikely to displace the U.S. dollar as the dominant currency — especially considering the lack of a stable currency among the group.

Question: “How much U.S. debt does the BRICS+ group own?”

Answer: The U.S. Treasury releases monthly “Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities,” which indicates that Brazil, India, China and Saudi Arabia own about 4% of total U.S. federal debt — down significantly from previous years. If you assume that other BRICS+ countries own half of the debt not assigned to other major holders, the number would increase to about 6%. So, while the dollar amounts are large, the ratio is small.

Question: “Can BRICS+ countries avoid buying U.S. commodities?”

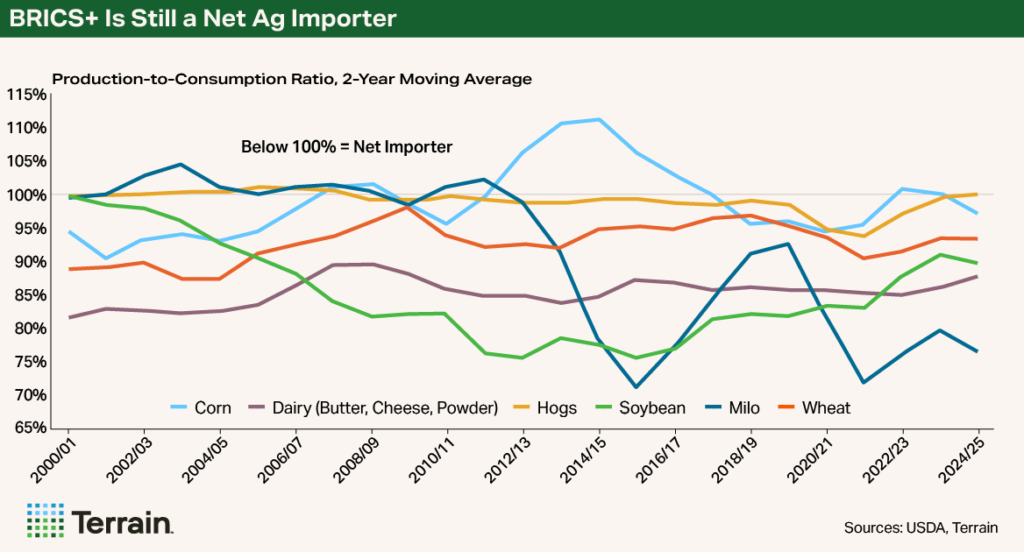

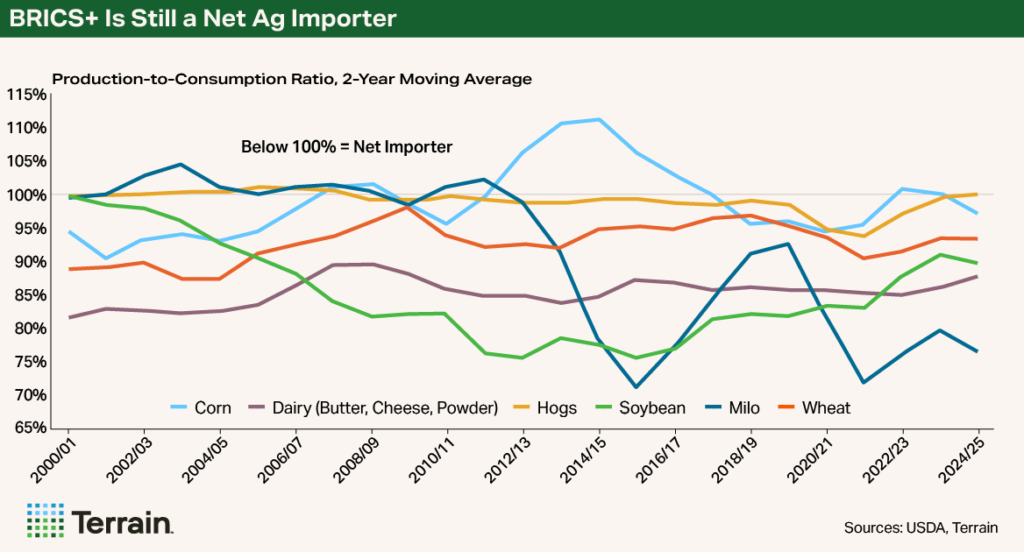

Answer: For agriculture, the group is still more a consumer than a producer (hence why BRICS+ had courted Argentina for its agricultural production). For example, if you divide total production by total consumption for key commodities, the balance is below 100%. Thus, in aggregate, BRICS+ is still a net importer.

In the long run, the population and consumption dynamics could change (see Terrain’s work on long-run global population trends). But even if BRICS+ nations traded just among themselves, they would still need imports, and countries that depend on Brazil would need to look elsewhere (Europe, for example). So, while the group will likely continue to move away from U.S. agriculture, it is unlikely that it can completely eliminate the need for our products and still fill export demand outside of BRICS+.

The risk for the U.S. farmer is that BRICS+ could encourage members to boost their own agricultural production, chiefly Brazil. An increase in global production would weigh on global agricultural stocks and dampen prices. However, related factors such as a large-scale land conversion, facility upgrades and labor force training would push the impact into the longer term.

BRICS+ Power Still Building

BRICS+ will continue to try to move away from the U.S. and the West. The group has the economic size and population base to wield global influence. However, the influence of BRICS+ is likely to play out over the long term due to the relative youth of the group and lack of coordination between many countries that are geographically and geopolitically diverse. In the immediate term, BRICS+ is unlikely to displace the U.S. dollar as the standard-bearer of global currency, nor can BRICS+ produce enough agricultural goods to be a self-sufficient trade bloc.

Endnotes

1 Beth Kowitt, “For Mr. BRIC, Nations Meeting a Milestone,” June 17, 2009, CNN Money, https://money.cnn.com/2009/06/17/news/economy/goldman_sachs_jim_oneill_interview.fortune/index.htm.

2 Oliver Stuenkel and Margot Treadwell, “Why Is Saudi Arabia Hedging Its BRICS Invite?” November 21, 2024, Emissary, https://carnegieendowment.org/emissary/2024/11/brics-saudi-arabia-hedging-why?lang=en. See also: “Indonesia Joins BRICS Bloc as Full Member, Brazil Says,” January 6, 2025, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/world/indonesia-join-brics-bloc-full-member-brazil-says-2025-01-06/.

3 “World Economic Outlook (October 2024),” International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets/WEO.

4 Marcela Ayres, Bernardo Caram and Lisandra Paraguassu, “Brazil Nixes BRICS Currency, Eyes Less Reliance on ‘Mighty’ Dollar,” February 13, 2025, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/markets/currencies/brazil-nixes-brics-currency-eyes-less-reliance-mighty-dollar-2025-02-13/.

5 Carol Bertaut, Bastian von Beschwitz, and Stephanie Curcuru, “The International Role of the U.S. Dollar Post-Covid Edition,” June 23, 2023, FEDS Notes, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-international-role-of-the-us-dollar-post-covid-edition-20230623.html.

6 Robert Greene, “The Difficult Realities of the BRICS’ Dedollarization Efforts—and the Renminbi’s Role,” December 5, 2023, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/12/the-difficult-realities-of-the-brics-dedollarization-effortsand-the-renminbis-role?lang=en.

7 “Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves,” December 20, 2024, IMF, https://data.imf.org/?sk=e6a5f467-c14b-4aa8-9f6d-5a09ec4e62a4&deliveryname=dm14395&deliveryname=fcp_3_dm15445.

Terrain content is an exclusive offering of AgCountry Farm Credit Services,

American AgCredit, Farm Credit Services of America and Frontier Farm Credit.